Treat Twitter like any other platform … be fast and first but not at the expense of being right

The attacks in Paris presented challenges for journalists’ use of social media

On a panel about the future of journalism at Oxford University earlier this month, a fellow speaker spoke passionately about what he termed the ‘democratisation of news’, writes James Toney.

Everyone is a publisher now, he said, everyone is a journalist with a Twitter account or broadcaster with an app like Periscope, us ‘pros’ don’t stand a chance.

And, of course, the attacks in Paris were trending on social media long before the BBC or Sky News or radio stations went live with reports, the first stories appeared online or initial alerts were pinging in on the newswires.

It’s certainly true that journalists don’t have a monopoly on the who, what, where and when and yet events in Paris underline the importance of separating news from noise – and why we must accurately tell the story of the why and how.

It’s an early lesson in journalism careers that your credibility is everything – hard-earned reputations can be lost with one bad editorial decision, ours is an unforgiving business.

But the attacks in Paris on Friday November 13th were not the finest hour for journalists on Twitter.

It’s impossible to apply professional editorial standards to social media but it is possible to apply professional editorial standards to how journalists use these emerging platforms, either as forums for pushing our own content and comment or sourcing stories.

Of course Captain Hindsight, whose alter ego also happens to be reporter Jack Brolin, is never wrong. We’ve all tweeted things we later or quickly regret or have retweeted something that makes us look a little stupid.

However, when it comes to a story of such significance, we must be more careful.

Identifying yourself as a journalist on your Twitter profile comes with a responsibility. You can’t hide behind ‘retweets don’t equal endorsement’ because they do – you are what you tweet and you are what you retweet.

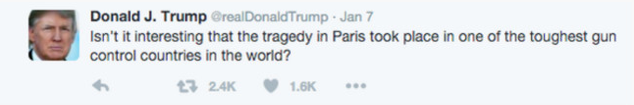

My timeline had too many journalists referencing a rather crass tweet from Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump. The only problem was he’d posted that message back in January, after the Charlie Hebdu attacks.

Context is crucial in matters like this, so take your time and double check the date – it takes seconds.

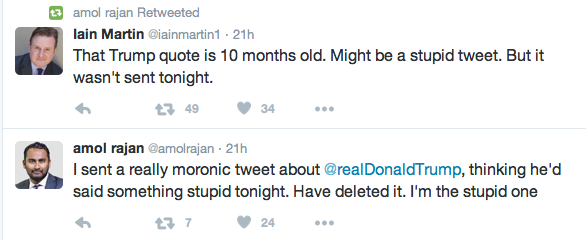

Some quickly spotted their error – or it was pointed out to them (in the rather gleeful way people like to do on social media) – and casually deleted their post and tried to pretend it didn’t happen.

More credit goes to those who publicly admitted their error – such as Independent editor Amol Rajan.

And then there were the hundreds of people – including many journalists – who retweeted a report on the Algerian website, El Manchar, that the French president, Francois Hollande, had suffered a stroke and been rushed to hospital.

If you were writing/broadcasting a story that important would you rely on a report published on a website you’d probably never heard of?

Would you take time to investigate the reliability of the media outlet who are reporting it?

If everyone was referencing the ‘news’ from a single source, would alarm bells ring?

Would you be concerned if Le Monde, Le Figaro or France 24 were strangely silent?

You don’t need to have spent more than a week training for your NCTJ Diploma to answer no, yes, yes and yes to those questions.

Journalists will never be first on a breaking news story like Paris – and they probably shouldn’t be. While Joe and Jane Public tweet immediately without consideration of reputation, verifying information takes a few more seconds and is a vital part of the editorial process.

A simple check of the El Manchar website reveals this in their own about us section:

El-Manchar est un site d’informations fausses et complètement saugrenues. Il a été créé dans le seul but d’explorer le champ de l’absurde. Aussi, les articles qui y sont publiés, ne renvoient à aucune occurrence du réel mais juste à des occurrences du possible.

Even if you’ve forgotten all your GCSE French – paste it into Google Translate and you’ll get this:

El- Manchar is a site completely false and absurd information. It was created for the sole purpose of exploring the absurd the field. Also , the articles published therein, does not refer to the actual occurrence but just occurrences possible.

It would have taken less than two minutes to spike that speculation.

Surely if you are reporting such a seismic story about such an important individual, especially against the backdrop of the unfolding events in Paris, it’s worth taking the time?

Making it first and fast is obviously important but making it right is always much more important.

We are constantly being told social media is just another platform for our journalism – and yet we seem to apply more casual standards to our tweeting than our writing or broadcasting.

It’s a mistake and it means the differential between professional and trained journalists and the ever-growing legion of citizen reporters will soon be indiscernible and that’s not good for anyone’s long-term career prospects.

For example, many retweeted a months old Vine of the lights going out on the Eiffel Tour (like it had happened on the same night) or reports of a fire in the vast ‘Jungle’ refugee camp near the French port of Calais, with pictures that were taken earlier this month.

Worst still were those that gave credence to totally unfounded speculation that it was some sort of revenge attack for what had happened earlier in Paris.

Time and time again, when a story like this breaks, respected journalists fall into the trap of tapping out a tweet that they wouldn’t think of filing in the traditional context.

The Independent on Sunday’s chief political commentator John Rentoul tweeted just eight words – ‘Will Corbyn say France made itself a target?’.

It’s a sentiment that would never have made his column and within seconds his account was ablaze with condemnation. To his credit he was quick to delete it and pen an apology, the journalists equivalent of drinking a pint of hemlock.

Paris was also another test of the ethical editorial decisions that need to be made without the benefit of time to pause and reflect.

Le Monde reporter Daniel Psenny bravely recorded the horrific scenes of frantic, screaming and wounded victims fleeing from the attack at the Bataclan theatre.

After filming for a few minutes, he went downstairs to help someone who had collapsed in the alley outside his flat. He was then shot in the arm and is now recovering.

Some news outlets used his footage unedited, including his own newspaper. Most broadcasters made the decision to blur or not screen the more disturbing elements of the recording, even though no-one could be identified.

Some showed restraint with the huge amount of user-generated content, pictures and video, that were available and some did not.

It’s a new editorial world out there but some traditional journalism values wouldn’t go amiss to help police it a bit better.

And, while we’re at it, we should probably all know the difference between the French and Dutch tricolor.

* James Toney is the managing editor of national press agency News Associates/Sportsbeat and responsible for our award-winning NCTJ accredited journalism schools in London and Manchester.